When NZ media write a piece on what it’s like living under the veil in NZ, you can bet they will leave out what is preached in the mosques here, such as Gamal Fouda’s Right’s of Husband video reveals. While his talk was given straight form the Quran, this website contains a substantial provides insight as to how NZ Muslims interpret the rest of the Quran.

Lynn, a New Zealand-born European, took on the name Siti Aminah after her conversion to Islam while living in Malaysia in the late 90s.

Although she still professes to be a firm believer of the faith, Ms Aminah said she has had to lead “a double life” since returning to New Zealand nearly 10 years ago.

“I have been wearing the hijab (a veil that covers the head and chest) since I became a Muslim, but that became an issue when I came back here,” said the 47-year-old customer relations officer. “For months I could not find work and I suspect a lot had to do with the hijab because I landed a job after the very first interview I went to without wearing one.”

She did not want to be photographed for this report, and spoke to the Herald on the condition that she was identified only by her Muslim name. Today Ms Aminah goes to work without the hijab, but wears it outside work and when going out with friends.

“It’s not that I am embarrassed about my faith or anything, but I lead this double life because I still have to make a living,” said Ms Aminah, who was raised a Catholic. “In New Zealand, people get unfairly treated and face prejudices when they are visibly different, even in dressing.”

Tomorrow, about 150 Muslim women from across the country are expected to gather at Zayed College for Girls in Mangere for “Wake Up Muslimah”, a women-only Islamic conference.

Participants at the three-day forum will discuss issues facing Muslim women here, including the status of women in Islam, family violence and a session about how “a man is not a financial plan”.

Dr Zain Ali, head of the Islamic Studies Research Unit at the University of Auckland, said the veils of Islamic women – such as the hijab and burqa – remained a “hot button issue” in many Western nations, including New Zealand.

This month, police said a 15-year-old girl who suffered a broken nose and tooth after being allegedly bashed by her father was asked to hide her injuries under a burqa, a full Islamic covering.

In 2011, a burqa-wearing 18-year-old English language student from Saudi Arabia was left crying on an Auckland street when a bus driver refused to let her board because she refused to remove her veil.

Islam is one of the fastest growing religions here, with the number of followers rising from 36,153 to 46,194, according to the latest Census figures.

Dr Ali said immigration and natural births were the main contributors for the growth, although he had noticed an increase in the number of conversions.

“Muslim women face the same challenges as any other women in New Zealand … if it’s not the scarf, then maybe it’s your accent, skin colour or having a non-anglicised name.

“But if you’re a Muslim here, you will have a combination of all four to contend with because most Muslims here are migrants.”

A University of Auckland School of Business survey in 2005 found having a Chinese or Indian name raised a job applicant’s chances to be considered unsuitable by Kiwi employers.

Dr Ali said issues facing Muslim women here included relationships, especially with non-Muslims, parental expectations and education.

He said wearing a burqa was not a religious requirement, but a cultural one in certain Muslim communities.

The University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research this month released the findings of a survey it conducted in seven Muslim-majority countries (Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Turkey) on how Muslim women should dress in public.

Respondents were given a card depicting six styles of women in headdress, ranging from a fully-hooded burqa and niqab, to the less conservative hijab and one of a woman wearing no head covering at all, with the question: “What style of dress is appropriate for women in public?”

Most respondents, 44 per cent, found a white hijab which completely covered a woman’s hair and ears to be most appropriate, with just 2 per cent choosing the fully-hooded burqa.

Dr Ali said it was difficult to interpret the findings fully because demographic breakdown, including results by gender, were not included in the release of that survey.

The history of the veil is a complex one and some studies have found it to predate Islam by many centuries, dating back to Assyrian kings. As Islam reached lands where the regional practice included the covering of women, the practice was adopted as a Muslim practice there.

Some Muslim women, such as those belonging to Malaysian-based Sisters in Islam are opposed to women being forced to wear the burqa.

At a forum at AUT University in 2011, the group’s executive director Ratna Osman said the burqa was “an affront to human dignity” for those forced to wear it because it was not a requirement in Islam.

Islamic Women’s Council of New Zealand spokeswoman Anjum Rahman agrees the burqa is not a religious requirement. However, she said women had the right to choose the dressing they feel comfortable with.

“A woman’s body is her own private space, and she has every right to choose to cover herself up without having to be judged or penalised for doing so,” she said.

Ms Rahman said the main issue Muslim women faced in Western societies was “the notion that we are victims and victimised and oppressed” despite their contributions at all levels of society.

“When a young (Muslim) woman goes for any job interview, first she has to prove that she is not all of those things, then she has to shine above all the other candidates.”

Two burqa-wearing women who came to Auckland from Saudi Arabia as international students were invited to be interviewed for this report, but they declined.

However, women who wore the hijab said they were happy to be wearing them and saw it as giving them a sense of identity as Muslims.

Alena Katkova, 29, a Russian Muslim convert, said people showed her “more respect” since she started wearing the hijab, a feeling shared by University of Auckland student Rawand Shiblaq, 23, originally from the Palestinian Territories.

Sahar Farhat, 23, who works as a co-ordinator at the New Muslim Project, saw the hijab as a symbol of freedom that helped her connect to God. Saphiya Zaza, 23, a Lebanese Kiwi, saw it as “more than a scarf” which affected her “character, interactions and relationships” with others.

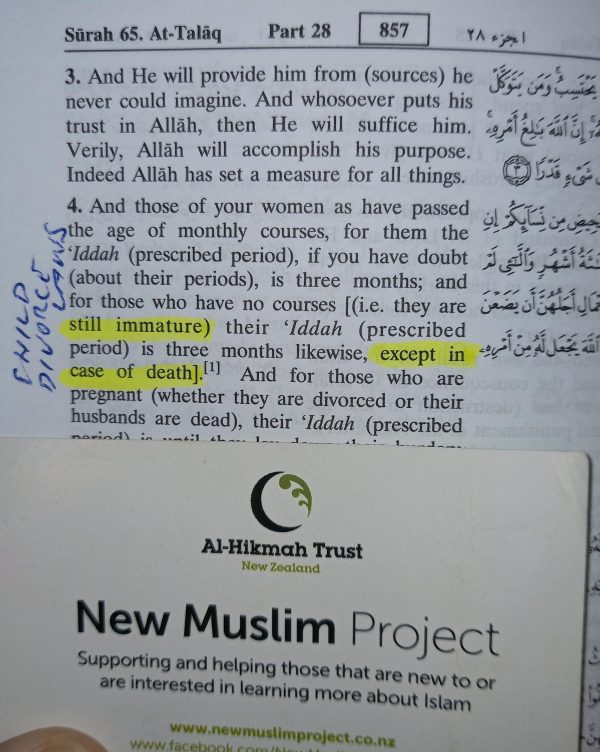

Auckland based New Muslim Project, also training for Aotearoa Maori Muslim Association, offer the clear Sadui Qurans to young kiwi men clarifying divorce laws for child brides.

Muslim women reveal challenges

This weekend, Muslim women from around the country will gather in Auckland for Wake Up Muslimah, a women-only Islamic conference. Here, five women, including two converts, tell the Herald about their lives and the challenges they face in living their faith in New Zealand

• Alena Katkova, 29, call centre operator, from Siberia, Russia

“I was born in Russia, actually the USSR where there was no religion and I came to NZ in 2008, a country with many cultures, nationalities and religion. When I started studying at AUT I met several students who were Muslims, and I got curious and started asking questions and that’s how I got to Islam. It changed my life a lot, to be honest, especially personality wise. Before I converted, I used to go out with friends partying and clubbing, but all that has stopped. Since I started wearing the hijab, how people treat me has changed and I think I now get more respect. In Islam we are not supposed to shake hands with men, or hug and kiss anyone who is not your relative, so I don’t do it. If I greet men I will just say “nice to meet you, but I’m sorry my religion does not allow me to shake hands with you” but with a smile they understand, and New Zealand is a very accepting country. However, there are challenges with my family, and even my younger sister still cannot understand or accept the fact that I am now a Muslim.

“In Russia, people still think of Muslims as terrorists because of what they see and hear in the media. I feel comfortable wearing the hijab, but when I’m thinking about changing jobs, because my qualification is in teaching, I am always thinking if they will actually accept me as a teacher here.”

• Siti Aminah, 47, customer relations officer, NZ-Pakeha

“I am single and was drawn to Islam while I was working as a teacher in Malaysia in the 1990s. I was raised a Catholic, but in my search for God, I found my answers in the Islamic faith. However, while I believe strongly in the spiritual aspect of the religion, the cultural aspect can make the faith journey a lonely one for someone who is a single, white female. In Malaysia, you’re not supposed to mingle with males and dating is out of the question, maybe that’s why I’m still single.

“Coming back here nearly 10 years ago, the challenge just gets bigger because I have been wearing the hijab since I became a Muslim, but that became an issue when I came back here. I went for interviews wearing the hijab and for months I could not find work, and I suspect a lot had to do with the hijab because I landed a job after the very first interview I went to without wearing one. In my job, I have to deal with people so I go to work without the hijab but wear it outside work or when I’m out with friends. In New Zealand, people get unfairly treated and face prejudices when they are visibly different, even in dressing and that’s a fact. It is also difficult dealing with people who are used to kissing on the cheek as a way of greeting … and having to tell them my religion forbids us from doing so.”

• Sahar Farhat, 23, New Muslim Project co-ordinator, from Afghanistan

“I was born in Afghanistan but went to school in Pakistan for a while before moving to New Zealand. When I came here, I knew a bit of English, and because I am friendly and like to talk to people, I didn’t feel too isolated. I came at a time when the September 11 attacks happened, and I had guys at school coming up to me saying things like ‘is Osama bin Laden your uncle?’.

“I was born a Muslim in a Muslim family, but I only started wearing the hijab less than two years ago. I think even if you are born a Muslim, there will come a certain point in your life when you decide whether you want to take your faith seriously or not, you make a conscious decision especially if one is deep and more of a thinker and spiritual. Islam encourages us to think and question. And studying philosophy and sociology at university encouraged me to question and analyse things more. I decided to study more about religions, and as I studied further I found that all the religions have the same message pretty much. But Islam made the most sense because it was more rational and provided the most direct connection with God. It is a correction and completion of all the religions.

“Since I started wearing the hijab, even some members of my family started treating me differently because even though they are Muslims, it was more cultural rather than spiritual. To me the hijab is about freedom and the main essence of Islam first of all is about freedom and liberation, and for example by putting on the hijab I free myself from my own ego and I connect to God and be in peace with myself and others around me.”

• Saphiya Zaza, 22, University of Auckland student, NZ-Lebanese

“Islam is very communal. Our NZ community works hard to keep us united. The Eid day celebrations, for instance, are not created by an event planner, but by engineers, students and business owners who utilise our community’s resources to bring everyone together. I love Islam’s sense of community. Although we are all individuals – we are individuals as part of a whole – we are all brothers and sisters. I love walking down the street and saying our greeting ‘assalam alaykom’, or peace be upon you, to other Muslims.

“Part of what I love about the scarf is that it identifies me as Muslim. But the hijab is more than a scarf – it affects my character, interactions and relationships with people. In this sense it creates a symbolic barrier that creates respectful relationships between myself and males. I don’t perceive this barrier as negative. Rather, it is one that I am grateful for, especially in a western country. As a Muslim, I pray five times a day; unlike the Middle East, which has the call to prayer, in NZ we rely on mobile phone apps to remind us it’s prayer time. I don’t view prayer as a hassle but as a spiritual, liberating, uplifting experience that reminds me of my purpose in life.”

• Rawand Shiblaq, 23, University of Auckland student, from Palestinian Territories

“Being in a university environment, I don’t think it is an issue being Muslim at all. A big part of Islam is family and society and playing a part in society, and even if we meet all the principles and obligations of prayer and fasting the religion teaches us that we must go out and contribute to society. At university, it isn’t uncommon to see Muslim females wearing the hijab around campus. While wearing the hijab I feel a sense of respect given to me as a sign of understanding from my peers. As a Muslim, praying is an obligation and in the past I have prayed in public places like malls, beaches and parks and have never had people make any negative comments at all.”